By the time President Biden confirmed this past April that, just as he had promised during his electoral campaign, the US would completely withdraw from Afghanistan by September 11th, the anniversary of the destruction of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, the war there was the longest in US history. The 9/11 attacks had been the cause of the American intervention, and the military campaign was motivated by a combination of revenge and by the prudential calculation that by killing or capturing the attacks’ architect, Osama bin Laden, and destroying the Taliban government of Mullah Omar that long had sheltered, protected and enabled him, the US could stave off future attacks. Call it the imperialism of fear. After the campaign’s success, America’s fears ebbed but instead of this leading to the withdrawal of US and NATO forces, the fear gave way to hopes of the most utopian variety. This was how the limited (and in my view entirely justifiable) goals for the invasion of Afghanistan quickly morphed into an open-ended US and NATO occupation of Afghanistan that was increasingly justified as what in the dialect of the world of international relations is somewhat misleadingly and condescendingly called nation-building. One can oppose this, as I did and still do, but nonetheless see its logic. For it was straightforward Counterterrorism 101: the Taliban state had fostered global terrorism, ergo to ensure that terrorism did not again set down roots in Afghanistan, another kind of state had to be created and US forces had to remain until that state could stand on its own.

In international affairs, realism and idealism are usually supposed to be at loggerheads but in in reality, they have always been difficult to keep separate. The same goes for self-interest and altruism. After all, almost all empires from Babylon to Washington have justified their hegemony by claiming to pursuing some form of what 19th century French imperialists called the “civilizing mission.” But partly because of the influence of missionary Protestantism on US foreign policy in the first half of the 20th century and partly because the American self-conception is of the United States as much an idea as a nation, 1

the American Empire, far more than its British predecessor, has been peculiarly vulnerable to the idea that all nations aspire to be America and, with American help, can eventually attain that goal. Today, after the abysmal failures of American ‘democracy building’ in Iraq and now in Afghanistan, it is tempting to simply dismiss the idea of the democratic transformation of a society by a foreign, conquering power, but this is a distortion of the historical facts. The US occupations of Germany and Japan after World War II were instrumental in the democratization, or, more accurately, especially in the German case, the re-democratization of both of these countries.

Because of this, to dismiss the Washington foreign policy consensus over long decades that democracy building was neither an intellectual and moral fraud nor an impossibility may be convenient for both realist and leftist critics of US foreign policy in the era of the Pax Americana, but it oversimplifies and ignores too much. This is especially applicable, I think, to Afghanistan during the two decade-long American war. Was there an imperial dimension to what unfolded there? Self-evidently: at this point, surely only the diminishing band still clinging to the idea that the US is not an empire could deny this. But reducing what took place in Afghanistan between the fall of Mullah Omar and President Biden’s full withdrawal to a case only of the iron heel of empire crushing an Afghan population that wanted nothing more than for the US to withdraw is to badly mis-describe what took place in Afghanistan between 2001 and August of 2021. As Sarah Chayes, whose remarkable career in Afghanistan began with her reporting for the US National Public Radio Network, passed through her work running an NGO in Kandahar, before becoming a special advisor to the then Chair of the US Joint Chiefs of staff, Admiral Mike Mullen, put in recently on her blog, “Afghans did not reject us. They looked at us as exemplars of democracy and the rule of law. They thought that’s what we stood for.”

Romantic? No doubt there is an element of that in Chayes’ apologia. But anyone trying to understand what happened in Afghanistan over the past twenty years needs to start by accepting the fact that whatever else it was, it wasn’t simple. For Chayes, and for many of the reporters who covered the war – Dexter Filkins and C. J. Chivers come to mind as two of the best known of this group, and also among those who have been most vocal in decrying not just the way the evacuations at Kabul airport were handed but the timing and character of the withdrawal – the US era in Afghanistan was not a project doomed from the start but the story of opportunity after opportunity lost. One must be careful here. Western reporters, above all US reporters, have been accused of allowing their personal connections to Afghan colleagues and interlocutors as clouding their judgment about whether the withdrawal itself was right or wrong. The same can be said of officials of various Western NGOs and philanthropies working in the country. And though many of these people have angrily denied this – the angry storms on Twitter have been malignant even by social media standards – I think there is some truth to it just the same.

I base this on the fact that Western coverage of the American era in Afghanistan has been brilliant in its reporting of all the ways in which US policy in Washington and actions on the ground had been at best mistaken and often malignant. Sarah Chayes in her writings has focused brilliantly on the refusal of US policymakers to address the corruption in the Afghan government that, through turning a blind eye, Washington was in many ways not only complicit in, but responsible for. She also explored with both deep reporting and analytic brilliance the ways in which Washington refused to pressurize Pakistan to cease its role as the Taliban’s principal sponsor. For his part, C. J. Chivers along with a group of talented journalists, most of whom were Afghans, set up for the New York Times a project called the Afghan War Casualty Report. Over fierce US and Afghan government opposition, Chivers and his colleagues produced a weekly report of the casualties suffered by Afghan government forces and Afghan civilians, as well as US and NATO forces from Taliban and ISIS attacks.

Defenders of the US presence in Afghanistan are often accused by their realist and leftist critics of various forms of Orientalism. But this, I think, is to get things badly wrong – and again I write as someone who supported and, despite the fiasco of the evacuations at Kabul Airport, supports the Biden administration’s decision to fully withdraw from Afghanistan by the end of August. It is simply a fact that millions of Afghans welcomed the American overthrow of the Taliban and wanted American help in constructing a freer society, above all one in which women’s rights were guaranteed. Again, this was not a fantasy or some imperial trope forced on Afghan women of “White Feminism,” to quote a despicable new book by the identitarian left writer, Rakia Zakaria. Zakaria may not have hoped the US occupation would help Afghan women gain rights, but millions of Afghan women did. That is why dismissing the claims made by writers and analysts like Chayes, but also US officials, starting with George W. Bush, the president who made the decision that US forces needed to remain, is simply to maim reality in the interests of ideology. In his 2010 memoir, “Decision Points,” which is in fact one of the more underrated US presidential memoirs, George W. Bush wrote that, “Afghanistan was the ultimate nation building mission. We had liberated the country from a primitive dictatorship, and we had a moral obligation to leave behind something better.”

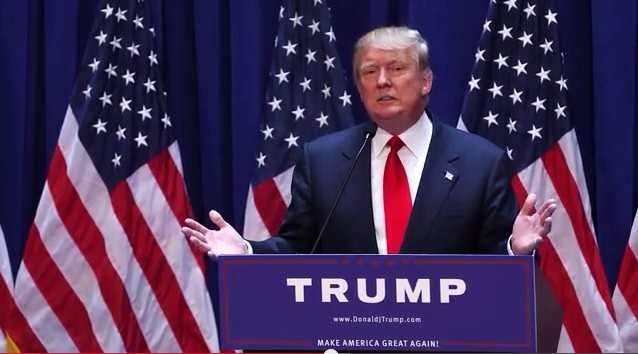

In a list of footnotes in an academic book, this might read: Good Intentions: see Road to Hell Paved With. Already in 2010, that is to say only halfway into the war, it was clear that nation-building was not working. But again and again, faced with evidence of this, Washington doubled down. When Barack Obama succeeded Bush as president, he reaffirmed the US commitment (Bush praises him heartily in “Decision Points”). Obama was no more successful than his predecessor had been. It was only when Donald Trump was elected that the US determination to pursue an open-ended nation-building project in Afghanistan was called into question. Before he was elected in 2016, Trump had been a fierce critic of a continued US presence. In an October 2015 interview with CNN, Trump insisted that, “We made a terrible mistake getting involved there in the first place,” and asked rhetorically, “Are [US forces] going to be there for the next 200 years?” In office, though, Trump distanced himself from that position, and in 2017 actually increased the US deployment. Still, at least according to some accounts, Trump continued to favor a US withdrawal and after he lost the 2020 election was determined to set that process in motion in a way that the incoming Biden administration would be unable to reverse. This culminated in a February 29, 2020, deal negotiated in Doha between the US special representative for Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad, and the Taliban’s political leader, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, which committed the US to withdrawing all its forces by May 1st of 2021.

With the feral incoherence that seems to mark everything he does, Trump initially took credit for Biden’s decision to withdraw. “I started the process,” he boasted at a rally in Wellington, Ohio, on June 26th of this year. “All the troops are coming back home. They [the Biden administration] couldn’t stop the process…Twenty-one years is enough, don’t we think?’ But as the scenes of despair at Kabul airport came to dominate the headlines, Trump took a diametrically opposing stance, calling the withdrawal “a disgrace,” and even demanding that Biden resign because of it.

Biden has himself insisted that Trump’s deal with the Taliban had limited his options. “The choice I had to make as your president,” he said in his speech to the nation on August 16th, “was either to follow through on that agreement [that Trump concluded with the Taliban] or be prepared to go back to fighting the Taliban in the middle of the spring fighting season.” But in an interview he gave three days later, Biden was adamant that no matter how badly things were going with the evacuations from Kabul airport, “There is no good time to leave Afghanistan.”

Trump was so widely despised and feared in elite circles in the US, including in the world of the neo-conservative interventionists who had served George W. Bush, kept their distance from Obama, but rallied to Biden during the 2016 electoral contest, that it should not be surprising that at least some of those who lament Biden’s decision have taken refuge in this idea that Trump left the new president no real choice save leaving immediately or remaining indefinitely. Others, and this applies particularly to Trump-loathing elites internationally, a group whose views might be coarsely but not inaccurately summed-up as shaping and being shaped by the editorial pages of the Financial Times and the Economist, go further. For them, there are striking continuities between Trump and Biden, not just on Afghanistan but on China as well. As the FT’s Edward Luce put it in an opinion piece titled “Biden’s America is confused – and so is the world,” “Viewed from anywhere in the US, the differences between Biden and Trump are stark. But the further you go from America’s shores, the more they narrow.’ [FT, 24 August] Besides the so-called international relations realists, an eloquent but comparatively marginal group in Washington, this view finds its echoes in the world of the serious left in the US, which is no longer the inconsequential matter it has been for decades because for the first time since the end of the Second World War that left is a force to be reckoned with in American national politics. 2

But in an America where Trump’s high bourgeois opponents could in various media, mainstream and social alike, style themselves unashamedly as “the Resistance,” as if the Santa Monica or the Upper West Side of Manhattan between 2017 and 2021 had been Lyon under the Nazis, the left view still gets little traction.

Instead, for most of Biden’s supporters in the foreign policy establishment, and the think tanks and university international affairs schools in which they work when out of government, by the mainstream media, but also by a surprisingly large number of human rights groups and major philanthropies – all places where Trump supporters are as rare as hens’ teeth – condemning Biden’s decision requires no ritualistic Trump-bashing before getting started. The consternation is that deep. Starkly put, the withdrawal has been greeted as simply being wrong from every perspective. First and foremost, it is deemed wrong morally. By withdrawing precipitously, the Biden administration is abandoning the Afghan people to their fate under cruel Taliban rule. But it is also wrong geo-strategically. The mainstream media has largely, though of course not entirely both reflected and amplified this view, with headlines more or less akin to that of an August 17th story in the Washington Post that was titled: “Withdrawal from Afghanistan Forces Allies and Adversaries to Reconsider America’s Global Role.”

In only a few weeks, the received wisdom among ‘the great and the good’ has become if the US was willing to leave the Afghans to their fate, how could the Taiwanese trust America to defend them? And what about Japan, and South Korea? “Beyond the local consequences,” thundered Richard Haass, a former senior State Department official who is now the president of the Council on Foreign Relations and is generally viewed as one of the leading figures in the American foreign policy establishment. “The grim aftermath of America’s strategic and moral failure [in Afghanistan] will reinforce questions about US reliability among friends and foes far and wide.” In this, Haass was treading a path all too familiar to anyone who has studied the Vietnam War. There, too, the Nixon administration and its supporters in Congress and the policy establishment insisted that the US could not withdraw from Vietnam because it would, as the formula had it, ‘lose face.’

Talk about Orientalism! And yet, I cannot think of a single example in modern US political history, including Vietnam, where a president has stirred up this degree of elite consensus against what he has decided to do.

But despite all the auguries that withdrawal from Afghanistan will embolden China regarding Taiwan, further encourage North Korean bellicosity, and confirm the Iranian government that it can take a hard line on the nuclear negotiations with the EU and the US, this very much remains to be seen. Where one stands on the matter – and it is worth keeping in the front of one’s mind that at this point we are all speculating – depends to a considerable extent on whether one accepts the ‘reputational,’ ‘lose face in one place, find yourself weakened everywhere’ view of Biden’s media and policy establishment critics or on what the Dartmouth international relations expert Jenny Lind calls the ‘credibility of power’ thesis, which holds that what matters is how the US deploys its power in the areas of vital geo-strategic concern to it. In other words, if the US expands its military commitments in Indian and Pacific theaters, what happens in Afghanistan is unlikely to matter much, if at all. I (probably unsurprisingly) tend to Lind’s view, and believe that that from a pure power politics perspective, contra Richard Haass US political and military credibility depends little on Afghanistan and much on how US war fighting capabilities are deployed after Afghanistan.

But this is hard, pure Machtpolitik. And even assuming the ‘capabilities’ view put forward by Lind, her Dartmouth colleague Darryl Press, and others is correct, Machtpolitik never has and never will satisfactorily address any of the moral issues involved. What was noteworthy in President Biden’s speech announcing complete and virtually immediate US withdrawal is that he repudiated completely George W. Bush’s nation building rationale. “Our mission in Afghanistan was never supposed to have been nation building,” he said. To the contrary, he insisted, the US “only vital national interest in Afghanistan remains today what it has always been: preventing a terrorist attack on the American homeland.” Where Biden has simply distorted the facts – and it is this that has particularly incensed people like Chayes, Chivers, and Filkins – is in his claim that American soldiers have been willing to die for a cause Afghan government soldiers have not been willing to sacrifice themselves for. To begin with, while US casualties have been nowhere near as light as they may appear at first glance,3

they pale by comparison to the losses suffered by their Afghan allies, which by some credible estimates run as high as 20% of all Afghans to have fought for the government against the Taliban. And if the Afghan army collapsed so quickly, that is in large measure because Washington tolerated an Afghan government that was for all intents and purposes a cynical kleptocracy. In short, when Biden claimed in his speech that, “We gave [the Afghans] every chance to determine their own future,” this is quite simply false.

In contrast, where Biden was right in my view was in insisting that he would not make the “mistake” of staying and fighting indefinitely in a conflict that is not in the national interest of the United States.” Not just right but radical in terms of recent American statecraft. Because in making this commitment, Biden is turning the page on one of the fundamental tenets of the so-called Long War, which was that, as he put it, that the US would attempt to “remake countries through endless military deployments of US forces.” Whether Biden will be partly, let alone wholly successful in this, remains to be seen, since, again, the policy establishment, the media, and many of the NGOs and philanthropies with global reach are sure to fight such a ‘reset’ tooth and nail. But for now at least, what Biden has done is to decouple the post-9/11 US security goal of permanent security for the homeland4

from that of nation building, which would have been inconceivable under Bush or Obama, though not, in fairness, under Trump.

This opposition is less surprising than it may seem at first. The recent turn of many of the most prominent media outlets toward adopting a kind of soft, demotic Wokeness in which high culture is often treated as an emblem of White Supremacy, even while – surprise, surprise – high capitalism is most certainly not, might lead those untutored in these matters to assume that the editors of these newspapers and magazines would be overwhelmingly for Biden’s decision to withdraw completely from Afghanistan. In reality, a number of the editors in question – David Remnick at the New Yorker is an exemplar of this – supported the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. Most, including Remnick, did later retract much of what they had said. But in 2021 as in 2003, they have never approached American Empire abroad as a wholly negative force, that is, in the way they now approach White Supremacy. In short, while racism equals barbarism, for them clearly imperialism does not. A meme on Twitter encapsulated this perfectly: it showed a canonical image from the Vietnam War of bombs cascading out of a B-52 bomber aircraft. But it showed them in two versions – a Republican one, which was undoctored, and a Democratic one, in which the words ‘Black Lives Matter’ are stenciled on the fuselage beneath the flight deck and a the rainbow flag symbol of Gay liberation painted on the tail.

Listening to the Afghanistan debate, it can almost seem as if this center-left worldview not only mixes the capitalism of J. P. Morgan Chase’s chairman, Jamie Dimon, with the most asinine (and, as many on the left try endlessly to point out, depoliticized), lowest common denominator Woke of the author of “White Fragility,” Robin DiAngelo, but now with also includes the last person one one would expect to find in the mix, the US military’s pioneering figure in counter-insurgency operations, General Edward Lansdale. The most powerful justification for all this, and, for understandable reasons it is particularly strong in certain human rights NGOs and philanthropies that since 2001 have set up very large programs in Afghanistan, is that if the US withdraws completely, the Taliban will destroy the substantial improvements in women’s rights, freedoms, economic autonomy, and the rest, that have been achieved over the past two decades.

These concerns are real. Indeed, there is evidence that the Taliban have already started doing this. No amount of sneering from the identitarian left at the concerns of US feminists for the fate of Afghan women, of the type Rakia Zakaria peddles in her “Against White Feminism,” and that as the UCLA professor and activist Sherene Razack once described as Western humanitarians “stealing the pain of others,” can change these realities. In fairness, as with every other grossly reductionist account of the world, no matter how distorted the uses to which they are put, it is undeniable that, historically, women’s rights have been used as moral justifications for empire. The classic case of this is the campaign by the British imperial authorities in India to proscribe and then suppress the practice of sati in which Indian women, upon the death of their husbands, would be expected to immolate themselves on the male’s funeral pyre.5

The underlying reality of British rule in India was, as Shashi Tharoor put it in his fine jeremiad against the Raj, “Inglorious Empire: What the British did to India,” “the British interfered with [Indian] social customs only when it suited them to do so.” But while women’s emancipation in Afghanistan was unquestionably used by defenders of the US war there as a moral justification, that emancipation was deep and widespread.

No, there is no justification for the claim that the British Raj did more good than harm to India. But the emancipation of women at least in urban Afghanistan has been that increasingly rare thing in this terrible world – a victory for humanity. One must be very careful here, very precise: to say that this is emphatically not to say that the increasing rights of Afghan women after 2001 was all or even mainly America’s doing. To the contrary, the struggle for women’s rights had many successes both under the Shah and during the Communist period, as a brief glance at any middle-class Kabul photo album from the 1960s or 1970s will show you. But those freedoms and rights were abolished when the Taliban took power in Afghanistan, and there is absolutely no reason to believe that this would have changed so long as they remained in control. Thus, even if one believes that the US presence was not the essential sine qua non for Afghan women to secure their rights, US withdrawal means they will again lose those rights.

It is not white American Feminists who are going to steal the pain of Afghan women, in Sherene Razack’s phrase, it is the Taliban. And all the anti-imperialist and identitarian cant in the world will not change this fact.

Does this mean that President Biden was wrong to abruptly end the US war in Afghanistan? I do not think so, and completely support his decision. I say this with no small amount of guilt and of doubt, which is why I have wanted to emphasize the price Afghan women will pay because it seems to me that too many of those supporting immediate withdrawal have refused to stare into the face of the gendered catastrophe that will result from it. In reality, the US had only two choices: remain in Afghanistan indefinitely, or leave, as even informed supporters of remaining in effect are acknowledging when they describe the total corruption of the Afghan state. If imperialism is the only answer, there is something wrong with the question. And in deciding to leave, despite the terrible cost, Biden opens up the possibility that the Long War will not, as so many have feared, be endless after all. That Long War has wreaked terrible damage on all our societies, both in the Global North and in the Global South. It has fueled the Surveillance State in countless ways across the globe. In the US, it has ushered in an era in which it is never quite clear whether the country is at peace or at war, which tremendously morally corrosive for any society. This obviously does not mean the drone strike war will end, including in Afghanistan itself, where Biden has already ordered one in retaliation for the suicide bombing at Kabul Airport. But it does mean that for the first time since the turn of the century it is possible to imagine counter-terrorism no longer being at the center of American strategy or American power. In a time without much hope on the international level, that is a reason for hope.

What else is there to say? There was no good way to end the US war in Afghanistan; the war had to end; and its ending has been terrible and may well grow more terrible still.

———–

Notes

1 In this US has always been less like imperial Britain, and more like imperial France.

2 This should not be surprising. The only meaningful historical precedent in the past hundred years to current crisis in the US, is that of the 1930s. Then, as now, the crisis was a multidimensional, systemic one of moral, political, historical, and memorial legitimacy. And then as now both the hard left and the hard right were powerful. By comparison, for all the hullabaloo about it both at the time and retrospectively, the 1960s was nothing of the sort.

3 2,218 US military service members have been killed in the two decades of the Afghan conflict. An approximately equal number of American Private Military Contractors have been killed, which testifies the extent to which the Long War has been privatized. This had led some analysts and pundits to describe them as having been comparatively light, and if the comparison is with Afghan government forces, more than 1/5th of whom are said to have died over the course of the conflict, this is correct. But a part of the reason for the low figure of American military killed in action is the astonishing progress in battlefield medicine that has meant that many who as recently as the First Gulf War of 1991 would have been killed in action instead have survived the wounds they suffered on the battlefields of Afghanistan. They number over 20,000 and even a short trip to the rehabilitation unit of any US military hospital, with its high numbers of patients who have suffered irreparable spinal cord and brain injuries, or lost multiple limbs, soon teaches you what that actually means.

4 On much of the left, ‘permanent security’ is viewed as morally a wholly illegitimate goal. A. Dirk Moses’ recent book The Problem of Genocide: Permanent Security and the Problem of Transgression (Cambridge University Press, 2021) is the most developed argument yet written from this perspective. Brilliant and frustrating at once, it is a work of daunting scholarship, profound moral commitment, but also to my mind utopian moral prescriptions so extreme that one can only assume that a historian of Moses’ high caliber has included them as a kind of provocation. Moses’ argument is nuanced, and I can obviously not do it justice in a footnote, but it is basically that the quest for permanent security is a kind of moral warrant for empire, unjustly affording great imperial powers, above all the US at the present time, the license to hunt down and kill anyone they deem a threat to the US homeland or, in principle, US interests, and erasing the fundamental distinction in international humanitarian law between legitimate military targets and illegitimate civilian ones. This leads Moses to call for outlawing military actions based on the goal of permanent security, and also for a ten-year limit on all occupations. (The Problem of Genocide, pp. 1-3 and pp. 509-511)

5 Even this at first glance seemingly clear cut case becomes more complicated on careful examination. Sati was certainly not widespread through all of Hindu India, and in fact seems to have been most common in Bengal. And it was not the British but the reforming Mughal Emperor Akbar in the 16th century who first tried to abolish the practice. Even the Raj’s actions in the 19th century seem to have been as much to do to pressure from the great Indian reformer, Raja Rammohan Roy, as it was the expression of Britain’s moral conscience.

6 What will happen to women in Afghanistan under Taliban rule will be a catastrophe. But many other disasters loom. The fate of higher Afghan education is a case in point. Since 2001, it has largely been funded by the US government, American private philanthropies, and monies from other OECD countries. That will all but certainly not be allowed to continue. As a medical physicist, Musa Joya, told the scientific journal Nature, “We spent all our money, energy and time in Afghanistan to build a brighter future for ourselves and our children. But with this kind of withdrawal, they destroyed all our lives, all our hopes and ambitions.”

David Rieff es escritor. En 2022 Debate reeditó su libro 'Un mar de muerte: recuerdos de un hijo'.